Around Milano

Running the ring of waterways round the capital of Lombardia.

Period

Jan - Dec

Elevation difference

1.166 m

Total Length

315 km

Duration

2/3 Days

I

Around Milano

00

Intro

01

Between the end of the world and a bygone Disneyland

02

The ramps of Brianza, Leonardo’s river and Giovanna’s shop

Our Friday afternoon is spent between two very different venues of Milanese cycling culture. The first is the famous Velodromo Vigorelli, where both Fausto Coppi and the Beatles performed in years past. The second, somewhat less well-known, is the mural depicting two cyclists in the Bovisa district: it’s in Via Codigoro, which with Via La Masa and Via Lambruschini forms the circuit of the now defunct Red Hook Crit. Nowadays cyclists compete in the PoliCrit, a criterium of furious night-time cycling that reaches almost 47 km/h along 1,350 metres, of which 340 all straight plus nine corners, six to left, three to right. I had read about the PoliCrit in Alvento#21 in an article by Davide Zeo Branca. And Zeo is now standing here in front of me.

Zeo hasn’t always lived in Milan, far from it. Until a few years ago he had a chalet in Gressoney where he would put up anyone who got there, in the mountains. In October 2010 he participated as a spectator in the first Red Hook Criterium ever to be held in Milan: ‘It was organised illegally,’ he recalls. Zeo is now a rider and very aware of the city’s social and urban problems: ‘Every day 600,000 cars enter the city and more or less the same number are already in it. That is why cycling, organising critical mass and working for a more sustainable city are all forms of resistance.

Differently from most car-drivers, cyclists in Milan can’t want to get out of the city. Partly because cycling in the city is never the best idea, and partly because a few kilometres out of the metropolis there are wonders that are just waiting to be reached by bicycle.

We finally set off. From the place where we slept, the Ostello Bello Grande, near the Milan’s Central Station, to the start of the Naviglio Grande, we need to cross the city centre: the Giardini Montanelli, then Via Manzoni, La Scala, Piazza del Duomo. When we arrive near Porta Ticinese, the Darsena becomes Naviglio Pavese and then Naviglio Grande. We follow the latter, all straight till we get to Corsico, the first town you cross as you leave Milan. Crossfit Corsico is written in huge letters on the walls of a gym. Next to it, a graffiti of Marvel’s Iron Man.

An image that clashes in form but not in substance with the only reference I had of Corsico, before getting here, namely that it was here that Carlo Galetti was born, winner of the Giro d’Italia for three consecutive years: 1909, 1910 and, together with his Atala teammates, 1911, in the only ‘team’ edition of the race. Galetti was nicknamed the Scoiattolo dei Navigli, the Squirrel of the Canals. This is how Gianni Brera described him in L’Avocatt in bicicletta, the lawyer on a bike: ‘Naturally coordinated like few others. Rather short, a little face like a squirrel, two cunning eyes and the long, thin nose of a shrew. [...] Nobody knows how he learned and nobody know where he trained’.

We finally set off. From the place where we slept, the Ostello Bello Grande, near the Milan’s Central Station, to the start of the Naviglio Grande, we need to cross the city centre: the Giardini Montanelli, then Via Manzoni, La Scala, Piazza del Duomo.

The Naviglio Grande is a sort of limes, a borderline, between two roads. On the other side of the canal, busy roads, motels, fruit vendors, petrol stations, fixed menu restaurants: all hit-and-run places, in short. On this side, along the cycle path, pedestrians and bicycles, mostly dilapidated farmsteads. A couple of turns near Trezzano break the straight and lead to the colourful town of Gaggiano. Having seen a small kiosk selling local blueberries, fruit and vegetables, one can truly say: here is the countryside!

It’s the first time I’m cycling in this area and I am surprised that I am covering so many kilometres on a cycle path that is both wide, far from the traffic and well paved. Since the day is particularly pleasant, we opt for a detour south: the abbazia di Morimondo is just half a dozen kilometres from Abbiategrasso. The towpath along the Naviglio di Bereguardo, a canal created as far back as the 15th century as a waterway for transporting goods from Pavia to the Naviglio Grande, is narrower than the previous one, more rural and with more people on bicycles.

Everything in Morimondo started with the Cistercian monks about 800 years ago. In the abbey, there’s two things you shouldn’t miss: the cloister, in which the monks used to study lectio divina, and the chapter house, in which a large planisphere is dotted with places where Cistercian abbeys stand around the world. Morimondo was founded in 1134, the first Cistercian abbey in Lombardy, and it bears the name of the French mother house of Morimond, at Fresnoy-en-Bassigny, in Alta Marna.

In front of a photo depicting the Pilgrim’s Arch in the 1920s, in which a large Humber Cycles advertisement can also be seen – not so different from today – Paola, a guide who knows every stone of the abbey, tells me one last story.

According to some, the name Morimondo, that sounds a bit like ‘dying world’ in Italian, may derive from the fact that once here, beyond the abbey, there was only marshland and desolation. The civilised world, in short, died at this abbey. Even our cycling tour ends here for today, at the southern border of Morimondo. Time to go back to Abbiategrasso and beyond.

Another surprise – and we have only travelled 50 kilometres – is Cassinetta di Lugagnano. From the bridge over the Naviglio Grande you can see a statue of the archbishop of Milan, San Carlo Borromeo, a walkway lined red tulips in white vases and a long succession of villas belonging to families of the old Milanese nobility. Several stone buildings almost entirely covered in ivy create a very different landscape from the urban one: cycling past a sequence of farmsteads, we are entering the Parco della Valle del Ticino.

The terrain becomes mixed. Plain gravel, loam, sand and coarser stones alternate for a splendid cycling experience. 95 per cent the route unravels far from car traffic: the only thing we have to watch out for is not to end up in the Ticino, which is digging up part of the area where the paths of the Riserva della Fagiana branch off.

Beyond Castelletto di Cuggiono, beyond Turbigo, is the smallest municipality in Milan’s metropolitan city: Nosate. Here we find what we have elected as an obligatory lunch stop, the Binda Bici Bar. A legendary meeting place for cyclists, the Binda is packed by pannolati of the highest calibre: those who smoke a pipe after parking their bikes, those who sport the elite odontoiatrica jersey, and those who want the BBB tote bag with a cycling Charlie Brown on it. The three most popular piadina, the barmaids assure us, are the Moser (speck, brie, salsa rosa), the Alzini (prosciutto crudo, brie, salad) and – especially if you have just won something important, because even piadina has to be earned- the Ganna (coppa, brie, mayonnaise).

A few hundred metres from the Binda, we leave the Ticino to be guided by another waterway: the Canale Villoresi. Lined with a very simple gravel path, the Villoresi starts from the Ticino at the Panperduto dam and after 86 kilometres flows into the Adda. It’s the second longest artificial watercourse in Italy, but you never get tired of cycling along it. The towns of Castano Primo, Buscate, Arconate and Busto Garolfo slip away as our bike wheels spin, sizzling on the gravel.

It was right here, where the Villoresi Canal intersects its course with that of the Olona River that Libero Ferrario was born in 1901, another of Lombardy’s many cycling champions of the early 20th century.

Continuing along the Canale Villoresi for about twenty kilometres, we’re intrigued by a turning towards Pinzano and the so-called Città satellite. In the 1960s, a large area, later absorbed within the Parco delle Groane, was turned into an amusement park and then gradually abandoned. In its heyday, in the 1980s, the park boasted, among other things, a go-kart track, merry-go-rounds, roller-coasters, a small zoo and an artificial lake. Now almost all of it has been abandoned, destroyed or removed.

The only place that still survives is Arnold’s, a bar run by retired couple Gaetano and Gilda, Sicilians from Castelvetrano. Mr Giorgio instead, has been cycling here for decades. He is almost eighty years old and remembers with longing when he used to take his young daughter here to have fun: «We used to have Disneyland… the park in Paris was right here».

At Senago we take the Villoresi back to Monza. We enter the city of Teodolinda when the sun has long since set: we will have to wait a little longer before we see the iron crown of the Longobard queen and the interior of the Villa Reale. We were also unlucky because it is not an evening when the Monza’s racetrack is open to bicycles: sometimes it is and it would have been marvellous. Anyway, after 150 kilometres on gravel what we really need is a stop at the Bergamina hotel, in the town by same name in the municipality of Arcore.

The following day, not only more distance, but also more elevation gain is ahead of us. After only five kilometres, near Gerno, we meet the Monza-Erba cycle path. The dirt road along the river Lambro is so much fun that – I never would have thought this – I wouldn’t mind cycling some more of it.

At Albiate a hallucination, perhaps a dream. The cycle-pedestrian path finishes and beyond a cement ramp. There it is: a climb.

Very short and cobbled, mostly between two small concrete walls; some call it Albiatenberg and it is just the beginning of a splendid up and down road along some plots of land. A fun series of hairpin bends downhill on a concrete stretch among the trees brings us to the ramp of the Carate-Calò station, with gradients of up to 20%.

The rollercoaster continues between Montesiro, Casatenovo and Missagliola, then, shortly after a small bridge over the Molgoretta stream, the road steepens quite dramatically. It is a rather rutted cart track, best suited perhaps for MTB-, known by cyclist of the area as the salita del cancello, the ascent of the gate.

When you reach the little square below the sanctuary of the Beata Vergine del Carmelo, you are on ‘a very high plateau, a balcony that rises, out of the fog, with a straight southward view; on windy days you can see everything from the Cisa to Monte Rosa’. Words of Mario Soldati, who was as much in love with Montevecchia as everyone who sets foot there.

Certainly Teo is, a cyclist and musician from Trezzo sull’Adda, who takes out his laptop to jot down a few crazy thoughts’ inspired by the view. He is the singer in a band whose name he reveals with a smile, Teo e le Veline Grasse. Behind us instead, is a commemorative plaque. It remembers Maria Gaetana Agnesi, who ‘of true mathematics and wise charity here young and octogenarian gladdened in peace her humble and great life’. Before a bicycle took me to Montevecchia, I didn’t even know of the existence of Maria Gaetana Agnesi, the great mathematician of 18th century.

A sharp left turn after the church of San Giovanni Battista leads us back to the dirt track. The road is downhill and you need to keep breaking, but squeezing the breaks is particularly pleasant when all around you there’s beautiful fields, pastures and views of Bagaggera, Valfredda and the Curone stream. Valleys of this kind seem unsuited to an altitude of 400 metres or so: it feels like being in Trentino and instead you are in Brianza. But what’s most surprising is that as soon as you to get out of the graffiti-covered subway of the Osnago train station, after a couple of pedal strokes, you’re already in Paderno and the scenery changes again, completely.

After a steep downhill stretch, in fact, ‘stopped the rustling of his feet in the foliage, everything silent around him, he began to hear a noise, a murmur, a murmur of running water. He listened; he was sure of it; he cried: “It’s the Adda!” It was like finding a friend, a brother, a saviour again. His tiredness almost disappeared, his pulse returned, he felt the blood flowing freely and warmly through all his veins, he felt the confidence of his thoughts grow, and the uncertainty and gravity of things largely vanish; and he did not hesitate to go deeper and deeper into the woods, following his friend, the noise.’

This is not my own arrival on the Adda river, of course, but that of Renzo Tramaglino in chapter XVII of Promessi Sposi. Manzoni’s youthful works also include an idyll called Adda, in which the river itself invites Vincenzo Monti to break the silence of its woods with a song. And Manzoni is not even the most prominent historical figure to be linked to the palindrome river: Leonardo da Vinci himself was employed by Ludovico il Moro to carry out studies and hydraulic projects in these areas.

Descending the Adda is somewhat bizarre. You hear the sound of water but rarely see the river. The canal on the right is the quiet Naviglio di Paderno and there’s no human sound to be heard, other than bicycle wheels or walking shoes. On the left there’s footpaths leading to a vantage point over the Adda canyon. One of these offers such a striking view that it’s said to have inspired Leonardo’s Le Vergini delle Roccie, The Virgin of the Rocks. Continuing along the cycle-pedestrian path, which once was trodden by horses pulling boats from the shore, one comes across two unique places. The first in the valley, the second is a few steps further up.

Two people are loudly playing cards, Scopa 15. On the table are two glasses of white wine, the bottle, an ashtray, some pizza, the score sheet and a pair of spectacles resting on a newspaper. Finally, a paper note: ‘Reserved for comrade Питер’. In Cyrillic it means Pietro, who’s one of the two players. The other, who’s losing, tells us that ‘we call this the Adda Vecchia, don’t ask me why. Maybe because for us the Adda is the one before the dams, before the canals, I don’t know. And that one, going down, it becomes a normal river again’. Here it evidently isn’t a normal river, and they call it Adda Vecchia.

Fabrizio, who hasn’t been lucky for a while, recommends I walk the thirty or so steps that separate the little bar where he volunteers, the Stallazzo, from the sanctuary of Madonna della Rocchetta. From there one has an incredible view of the river that a statue of Leonardo, with a grim and solemn gaze, points to with one hand, while the other holds some parchments. I leave the Stallazzo unwillingly, after a bresaola sandwich and a glass of wine, but I am only at about a third of the way and it is already midday.

Past the splendid art nouveau-style Bertini and Esterle hydroelectric power stations, the dirt track makes the route a true paradise for gravel bikes. The pastel colours of the landscape are perfectly enhanced by the decadent works of man built around the waters, until we reach Trezzo and the Taccani power station. Imposing and dark grey in colour, this building looks like something out of Gotham City, accidentally moved into the Bosco dei cento acri: this absurdity obviously makes it totally fascinating. Trezzo’s most incredible spot, however, is yet another. Beneath the castle built by Bernabò Visconti around 1370, beautiful concrete hairpin turns lead to the ancient port of Trezzo.

We momentarily leave the river Adda for the Naviglio Martesana and arrive at Groppello, a small town near Cassano: very quickly, the scenery changes from a gigantic wheel on the water to the archbishop’s palace, surrounded by trees in autumn colours.

In Cassano instead, the advice is to forget for a moment what the cycling computer says and immerse yourself in the Parco Botanico Isola Borromeo. The garden is home to many species of plants with beautiful names (tremulous poplar, black alder, viburnum opium) and small bucolic pictures: in a little pond in the northern part of the island, for example, storks – or were they swans? herons? – were peacefully passing their time.

Further down the Adda, the landscape changes again. Now we really are on the plain. Crossing through the bosco Mortone and the river beaches of Boffalora is a real wonder. The gravel paradise still doesn’t end at Montanaso Lombardo, where the Belgiardino and Muzza canals (the latter has the majesty of a French watercourse in certain stretches) lead to Lodi Vecchio. Those with good legs will arrive here around lunchtime: after a generous snack of Lodi cheese, a visit to what remains of Laus Pompeia is a must. This was one of the first dwellings of the people of Celtic origin who lived in the Po Valley as far back as 600 B.C.

Passing through Sant’Angelo Lodigiano and Marudo, we quickly arrive at a rather unusual place, scattered as it is between Pavia and Lodi: there is not much to see in Bascapè, except for a place that made us discover yet another local story. In fact, here in 1962, in circumstances that are still unclear, a plane carrying Enrico Mattei, the then president of ENI, crashed killing everyone on board. Just west of Bascapè, a memorial commemorates this tragic event, one of Italy’s greatest mysteries.

The country roads continue well beyond Bascapè and Carpiano. Cultivated fields, tractors, dirt roads and the smell of manure give way to a splendid single track through the trees at Cascina Santa Brera. In just a few pedal strokes, past San Giuliano Milanese, we arrive at the abbazia di Chiaravalle, another place of culture in the area south of Milan that you mustn’t miss. Frate Davide walks me through the cloister and towards the abbey mill, joking about the hard life of cyclists, which is nothing compared to their ora et labora: every morning the friars’ alarm clocks go off around 3:30.

The way back into Milan, through the small town of Vaiano Valle, is gentle and far away from the traffic. I pass the Corvetto and Calvairate districts using fast roads; I realise that, even if I’ll have to cross the entire centre of Milan again, it would make sense to end the adventure at Rossignoli’s, a historic bicycle shop. Many have told me about it, but I’ve never been there before. Arriving in Corso Garibaldi, it’s impossible not to notice the red lettering on a white background and the yellow-lit shop windows, there’s Piero della Francesca and Raffaello in the nearby art gallery Pinacoteca Brera, but I decide to put them on my to-do list for the next time I’m here. Inside, I meet Giovanna, who runs the shop with her brothers. Her smile is contagious, and the two words with which she bids me farewell I think are the best wish that can be made to those who move around by bike, in Milan or elsewhere, for who’s about to finish their journey on their way to the station to catch a train, or for those who are about to start a long bikepacking trip: ‘Happy cycling’ she says.

Bike type

Gravel

* informazione Publiredazionale

Texts

Michele Pelacci

Photos

Federico Ravassard

Cycled with us

Jonas Lang

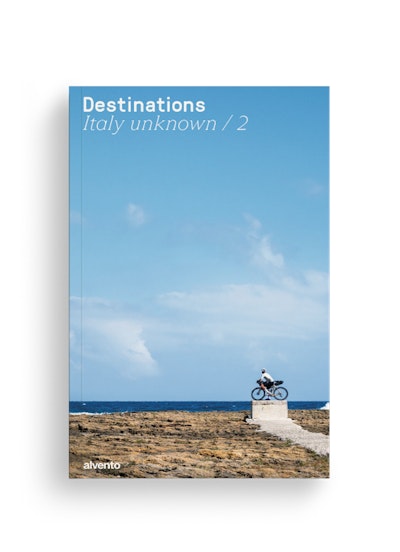

This tour can be found in the super-magazine Destinations - Italy unknown / 2, the special issue of alvento dedicated to bikepacking. 12 little-trodden destinations or reinterpretations of famous cycling destinations.