Off the radar

The unprecedented beauty of the Stelvio National Park’s dirt tracks.

Elevation difference

6.428 m

Total Length

191 km

Duration

3 Days

T

Off the radar

00

Intro

01

Bormio, Cancano Lakes, Stelvio: between restless waters and hidden paths

02

From Stelvio to Grosio: along ancient railways and Springsteenian gravel roads

03

Grosio, val di Rezzalo and the ascent to the Gavia Pass

On that day, along the 48 endless switchbacks of the South Tyrolean side, Coppi outdistanced everyone, including the Swiss champion Hugo Koblet. In so doing he took the pink jersey, and won his fifth Giro d’Italia the following day in Milan.

Conquering the Stelvio from the two canonical, sides, Bormio and Prato allo Stelvio, is a beautiful and memorable feat. Some of us, however, are predisposed to less conventional adventures – to a life less ordinary. The thought of exploring the more remote landscapes of the Stelvio National Park, riding off the beaten track, had a certain appeal to us. Thus, enriched by the myth of His Majesty the Ascent, we jumped on our gravel bikes. Lying in wait were dirt tracks, mule tracks and single tracks. Admittedly the routes we chose aren’t for everyone, but we reasoned it would be breathtakingly beautiful. Three days in Bormio — the base camp of our bikepacking experience — and up and down the Alta Valtellina. What, in a cycling context, could possibly be better?

Bormio is the nerve centre of the Alta Valtellina, the keystone of the roads that lead on one side to the Foscagno pass, Livigno and Switzerland; and on the other, towards Santa Caterina Valfurva, to the Gavia pass, the Camonica valley and the province of Brescia. Finally, over the Stelvio pass into the Venosta valley and Alto Adige, travelling backwards along the road that saw Coppi’s triumph in 1953.

Cyclists aren’t much interested in an easy life, so on day one we’ll ride the Stelvio from its lesser-known side. We’ll head from Bormio to Valdidentro, and then climb to the Cancano lakes. We’ll cross into the Müstair valley in Switzerland, climb up through the Umbrail pass, and conclude with the 2758 metres of the mighty Stelvio.

We wake early, and eat breakfast without much by way of fanfare. We’re primed and ready to go, and the desire to dive into this playground for cyclists is palpable. We’re accompanied by Angelo, by Matteo and by Daniele. He’s nicknamed Stelvioman, on account of his ridden this thing countless times. Following a final check of the bags, we climb aboard our gravel bikes and begin to make our way. We know that two-thirds of today’s route will be off-road, taking in mule tracks and single tracks. We’re excited about that, but we begin with good old-fashioned tarmac.

We warm-up is gentle enough. It’s the road leading to the Cancano lakes, via the snake-like switchbacks of the Torri di Fraele. Back in the 1920s, the Milanese company AEM built two separate reservoirs here. Collectively, the San Giacomo and Cancano constitute the principal water source of the entire Alta Valtellina.

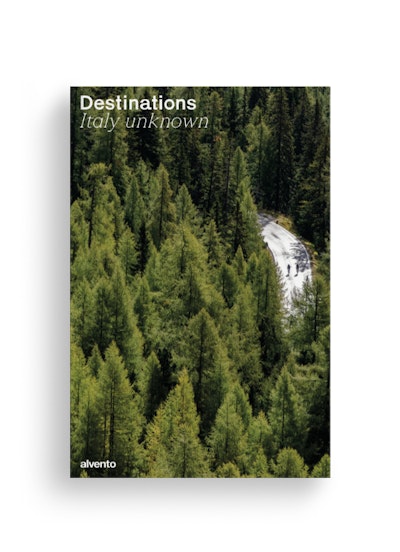

We reach the Rifugio Ristoro Monte Scale, finish line of the 18th stage of the 2020 Giro d’Italia, and here the riding changes dramatically as the adventure begins in earnest. We find ourselves alone, riding in stillness and in silence among the stones and branches of the dirt road which surrounds the lakes. The landscape shifts — it becomes rougher, more sturm und drang — by way of reminding us that this, fundamentally, is what cycling should be; direct contact with nature, at its most brutal if necessary. We’re immersed in a larch forest that seems to come straight out of a Grimm brothers’ fairy tale. After passing a picnic area, we head towards the Swiss border, although we see no customs — only stones to indicate the crossing.

We’re riding along routes that were once forged by intense trade Wine from Valtellina headed for Bavaria, and rock salt from the Tyrolean mines of Hall and headed for Italy.

We said it — we want to reach the Stelvio in the least obvious way possible. Having arrived at the Müstair valley in Santa Maria, we begin the ascent to the Umbrail pass on an asphalt surface. It is 13 kilometres long with an average gradient of 8.6%, leading into the last climb from Bormio. The Umbrail is hard at the beginning, with stretches above 10%, and more forgiving in the second part. In any case, it is a marvel made even more exciting by the thought that we will spend the night in the refuge up there, at the 2,758 metres of Cima Coppi — floating on our dreams of champions. These are the final numbers of the day: 56.4 kilometres covered with an elevation gain of 2,400 metres. Pretty tough.

After a night in a mountain hut, everything looks more beautiful, the abundant breakfast included. There, however, the fun stops. We hadn’t reckoned on the intense cold, and at 3,000 metres it’s savage, merciless. It’s 7 o’clock in the morning, and the descent is a war of attrition. The air up here is implacable, to the point of brutality. It’s violent, and it hurts. Descending this is very poetic after the fact, but right now it’s something I’d gladly do without.

We wear leggings, long sleeves, even winter gloves and anything warm we can find in our bikepacking bags.

This is the one that leads us to the gentle, secluded Scorluzzo lake, where there are the remains of fortifications from the First World War.

We then descend again, and at the third casa cantoniera on the Stelvio state road, we take the tarmac back down to the Braulio valley. Our love affair with unforeseen detours does not end here. We ride along the ancient switchbacks designed by the engineer Carlo Donegani — today closed to cars, and precisely for this reason of considerable charm and scenic impact.

After the first casa cantoniera, a sharp right turn directs us towards Boscopiano. A dirt road skirts the course of the newly born Adda river, then climbs to an altitude of between 1,800 and 1,900 metres and takes us back to the Cancano lakes. From here we take the hairpin bends of the Torri di Fraele, but in the opposite direction to that of the first day. The Torri di Fraele – ‘Fraele Towers’ – , together with the scale — ‘stairs’ — of the same name, are the ruins of a very old military outpost dating back to 1391. If you look closely, you can still see some steps carved into the rock. Along the winding path, pitfalls were arranged ad hoc, covered with thin branches to make unwary assailants fall into the void.

Approximately halfway down, we turn right onto a cycle path with a very special history. At the end of the 19th century, engineer Paul Decauville devised a railway that could be dismantled. The steel narrow-gauge tracks were easy to position and put together, almost like Lego bricks. Ideal for transporting goods like ore, wood, clay and peat, the Decauville railways were used extensively in the last century. And it is along the old site of one of them that we find ourselves cycling, after passing the Cancano dam and the Fraele Towers.

We ride along the Decauville cycle path to the village of Arnoga, about ten flat kilometres during which our legs relax and we enjoy the view of the mountains. The second great discovery of the day is the unexpected Verva valley and the ascent to the pass of the same name. The road is unpaved and very bumpy. When it rains here, the water often channels deep furrows with an Old West flavour, as if they came out of a Springsteen song. Our arrival at the pass is marked by a rock stele.

The descent is almost as demanding as the climb, and must be approached with caution. Along the way we come across the Rifugio Falk, near which we contemplate another of the countless expanses of water on this incredible day — it is the lake with the evocative name of Acque Sparse.

Finally, we swoop down to Grosio and arrive at the second pit stop of our three-day adventure. After 50 kilometres and 1,200 metres of altitude gain, it is definitely time for a couple of beers and bresaola sandwiches in the old town centre.

In the morning, before leaving Grosio, we cannot miss a visit to its castles. Perched on the hill overlooking the Rupe Magna, their crenellated and turreted walls rarely go unnoticed. There are two of them, San Faustino Castle, or Castello Vecchio (10th-11th century), and Visconti Venosta Castle, also known as Castello Nuovo (1350-1370). Both are now part of Grosio’s Park of Rock Engravings. We warm our legs up, put to the test by the previous two days, along the Sentiero Valtellina cycle path that connects Colico to Bormio along the Adda valley floor. Travelling by bicycle is the ideal way to discover the most beautiful villages in Valtellina. It transpires, though, that we’re not given to dawdling. We leave the sentiero at La Prese, and now the first challenge of our final day presents itself. It is the climb that leads to the authentic jewel of the Rezzalo valley.

Here we encounter the villages of Frontale, made famous by a song by Davide Van De Sfroos, and then Fumero.

We continue along an old military road that skilfully circumvents the rocky and ominous masses of Corno di Boero. We are cycling on a segment of the Bormio360 trail, an adventure trail designed for hikers and mountain bikers, which traces a loop — 140 kilometres in length with a total elevation gain of 6,200 metres — and embraces the mountain slopes of the five municipalities of the Bormio area: Bormio, Sondalo, Valdidentro, Valdisotto and Valfurva. It can be divided into several stages with the opportunity to spend the night in the refuges and mountain huts along the route (www.bormio360).

The valley now opens up in all its secret splendor, a pearl of the Stelvio National Park that no cyclist, for any reason in the world, should miss.

They say this valley was so secluded that it became a sanctuary for spectres and dark presences. Among them roamed the spirits of the so-called ‘confined’. Such were their heresies that they could find no peace, and indeed no place. They weren’t welcome in purgatory, much less in heaven, and even the devil himself spurned them. Rather they were banished to the most remote corners, to places like the Rezzalo valley. All of which strikes us as somewhat odd, given that it resembles paradise. Expanses of pastures alternate with larch forests and carpets of rhododendrons and blueberries. Suddenly we spot a small church with a tiny bell tower: it is that of San Bernardo. The landscape surrounding the parish church is breathtaking, dominated by the long meanders carved out by the Rezzalasco stream. Only the most restless souls, those of the cycle-tourer, could end up here.

Having arrived in the vicinity of Clivio, we are at an altitude of 2,000 metres. From here on up is where any proper cyclist starts to breathe. Oxygen is the secret of the heights. A little further on at the Alpe pass, as we venture out of the saddle, we notice some fortifications. It is another memory of the Great War: tunnels, trenches and blockhouses. Places forgotten by God. And rediscovered by cyclists.

Now however, it’s time for full commitment. A very treacherous single track awaits us. It is so rocky that in some places we raise the white flag. We continue on foot, undone by the hard law of cyclo-cross. Fortunately, the cruel path soon becomes a mule track again until we rejoin another mythical road. The tarmac that climbs to the Gavia pass. Reaching 2,652 metres of altitude, we could call it the Stelvio’s little brother. We are on the ‘noble’ side of the famous pass, the one that climbs from Ponte di Legno: a narrow, exposed road with no protection. The charm to this temple of cycling is unique. Particularly the highest section that precedes the long, curving tunnel uphill. Caution: it is poorly lit and the asphalt is very uneven. It must be ridden with the lights on (front and rear).

Once out of the tunnel, we’re close to the summit. The subsequent descent to Santa Caterina in Valfurva requires maximum concentration. When you descend the Gavia, you can't help but put your hand on your heart and think of the historic stage of the 1988 Giro d'Italia. On that day, an unseasonably heavy snowstorm swept over the top of the pass. It prevented the television cameras from filming, but the chaos which unfolded on the descent was the stuff of cycling legend. The frozen riders descended as best they could, but the whole thing was apocalyptic. It’s no exaggeration to state that those who didn’t abandon arrived in Bormio as zombies. Not Andy Hampsten, though. The American took the pink jersey from Franco Chioccioli, nicknamed Coppino because of a certain resemblance to the Campionissimo. Coppi – always Coppi. It was ever thus…

The arrival in Bormio has the sparkling taste of a journey completed and a feat accomplished. And today it is 63 kilometres and 2,274 metres of altitude difference. Not bad.

Bike type

Gravel

* informazione Publiredazionale

Texts

Giacomo Pellizzari

Photos

Paolo Penni Martelli

Cycled with us

Angelo Galbiati, Matteo Illini, Daniele Schena

Questo itinerario lo puoi trovare sul super-magazine Destinations – Italy unknown / 1, lo speciale di alvento dedicato al bikepacking. 13 destinazioni poco battute o reinterpretazioni di mete ciclistiche famose.